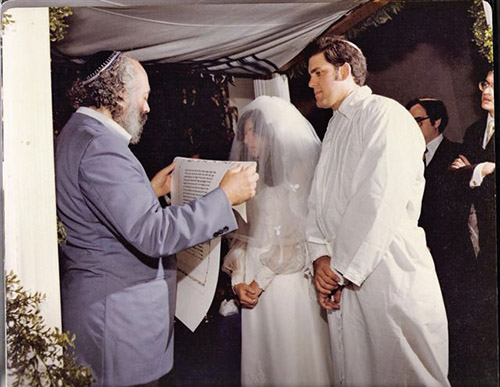

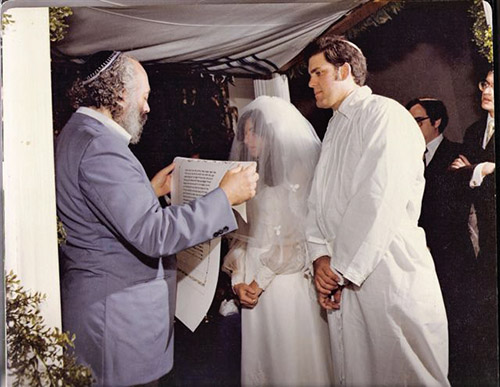

Over the centuries, a custom evolved in the Jewish community to use a tallit as a wedding chuppah. It is frequently a gift from the bride to the groom. When he wears it, the tzitzit (four fringes) representing taryag mitzvot (the 613 commandments) remind him that he is bound to his bride, to the exclusion of all other women. Similarly, the bride’s ring symbolizes that she is bound to her husband, to the exclusion of all other men. I attached my Shabbat tallit to the ceiling of our chupa, knowing that Shabbat would provide an opportune time for connecting with family and tradition, just like our wedding did. During our 39 years of marriage, I noticed my tallit has become a bit tattered and yellowed. In today’s consumer culture, I would likely bury the old one and go purchase the latest model. But that won’t happen, because I like the warmth of the original item.

The daily blessing on the tallit refers to protection and elevation. Until our wedding, it was my parents who were responsible to protect and elevate me; after that it would be my wife. My tallit surrounds me with plentiful memories. It reminds me of who stood under our chupa and witnessed the commitment that we both undertook, especially my parents (of blessed memory) and the decades of watching their marriage.

My parents weren’t keen on saying “I love you” in public. But I remember them demonstrating it in numerous simple ways. The daily hello and goodbye kiss was essential as was the good-morning and good-night kiss.

Dad checked Mom’s car daily…tires, oil and wiper fluid so that everything would be safe. Mom bought Dad record albums of opera and symphonies and converted them to cassette tapes because he loved listening to them in his car. I marveled at how, despite their different upbringings, they enjoyed many activities together. They also had diverse hobbies that they enjoyed separately. Dad was a mechanical engineer who loved skiing, boating and raising orchids. Mom, a teacher and pianist, was raised in the Midwest surrounded by social activism and fine arts. Her passion was creating magnificent glass tile mosaics, each having thousands of pieces that were meticulously cut and then glued into place. Mom was more emotional; Dad was more physical. Only after I was married did I realize that their marriage didn’t last despite their differences; rather it thrived because of them.

Concerning parenting skills, they were of one mind. When I broke a rule and needed disciplining, I received a deep-voiced reprimand from my father, “Your mother and I do not approve of your behavior.”

As a child, I was quite sad when my friend Jacob and his mother sold their nice house on our street and moved into the tall apartment building on Parkview Point. That’s when I first heard the “d” word. It was the ‘60s and the divorce rates in the United States were beginning to soar. I wondered how a family problem or argument could be so unresolvable that parents could actually divorce. And then came the night of the flying dishes.

My father decided to help his closest friend, Milton, in his run for city council of Miami Beach. For three weeks, he never came home until after midnight when everyone was asleep. Our nightly family dinners continued, but it was only Mom and her boys; we hardly saw Dad. My mother was fed up. She could not endure raising three sons by herself, and then things got nasty.

One night, my brothers and I awoke to the sound of Mom throwing dishes and screaming at Dad. My father convinced her to stop her tantrum by promising to immediately resign from Milton’s political campaign. Our house was quiet again, although in quite a state of disarray.

I couldn’t sleep that night because I assumed the “d” word was next and we would sell our house and move to Parkview Point. But the next morning, Dad brought Mom coffee and checked the fluids in her car. He took his early morning bike ride with his best friend Milton and resigned from his campaign. He apologized to Mom, kissed her goodbye and went to work. That’s the day I learned what forgiveness means in a marriage.

These are the warm memories that envelop me as I wear the tallit that served as our chupa. Ten years ago, one of the four tzitzit of my tallit tore off by accident, which rendered it unsuitable for use. I could have disposed of it properly by burying it, but I came to realize that when something precious breaks you don’t toss it, you fix it. That’s another lesson my tallit taught me about marriage.

By Alan M. Singer, Ph.D.

Dr. Alan Singer is a marriage and family therapist in Englewood and Highland Park, New Jersey. He has an 80 percent success rate in saving marriages on the brink. He is featured on the National Registry of Marriage-Friendly Therapists and the speakers’ bureau of the National Council of Young Israel. He counsels via Skype, blogs at www.FamilyThinking.com and is the author of “Creating Your Perfect Family Size” (Wiley). Married for 39 years, he and his wife are the parents of four grown children. Contact him at [email protected] or (732) 572-2707.